Imagined receiving – or being born with – a life sentence with no possibility of parole. The prison will be your own body. And in this prison, you may be electrically shocked into convulsions, or afflicted with bleeding in your brain, or gagged so you can’t speak, or shackled so you can’t move your arms or your legs, or even be denied light itself.

But people enduring conditions such as seizures, strokes, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and blindness don’t need to imagine any of that, because no matter how high their quality of life may be in numerous ways, they face those restrictions every day. In theory, brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) could be a pathway to “parole,” but according to Ken Shepard, one of the senior authors of the Nature Electronics paper “A wireless subdural-contained brain–computer interface with 65,536 electrodes and 1,024 channels,” current BCIs are no prison-break for most patients.

“Most implantable systems are built around a canister of electronics that occupies enormous volumes of space inside the body,” says Shepard, who led the project’s engineering, and is Lau Family Professor of Electrical Engineering, professor of biomedical engineering, and professor of neurological sciences at Columbia University.

But that doesn’t mean Shepard is offering no hope – far from it. Indeed, he’s on a team of researchers from the Columbia University School of Engineering and Applied Science and Stanford’s Enigma Project whose remarkable new BCI – the Biological Interface System to Cortex (BISC) – may offer permanent liberation.

Columbia University

As main clinical collaborator and Columbia assistant professor of neurological surgery Brett Youngerman explains, the BISC is a vast improvement for patients needing somatic relief that a BCI should be able to provide. “The key to effective brain-computer interface devices is to maximize the information flow to and from the brain,” says Youngerman, “while making the device as minimally invasive in its surgical implantation as possible. BISC surpasses previous technology on both fronts.”

That’s because unlike those bulky canisters that Shepard described, the paper-thin BISC, says Youngerman, “can be inserted through a minimally invasive incision in the skull and slid directly onto the surface of the brain in the subdural space.” Even better, the BISC has neither wires nor brain-penetrating electrodes, an improvement that reduces “tissue reactivity and signal degradation over time.”

So, what’s the secret to BISC’s superior design? Superconductors, a proven technology and manufacturing method which unlocks BISC’s future of mass production.

“Semiconductor technology has made this possible,” says Shepard, because semiconductors allow miniaturization that shrinks the processing might of computers from the volume of multiple bank vaults to size of a single wallet. “We are now doing the same for medical implantables, allowing complex electronics to exist in the body while taking up almost no space.”

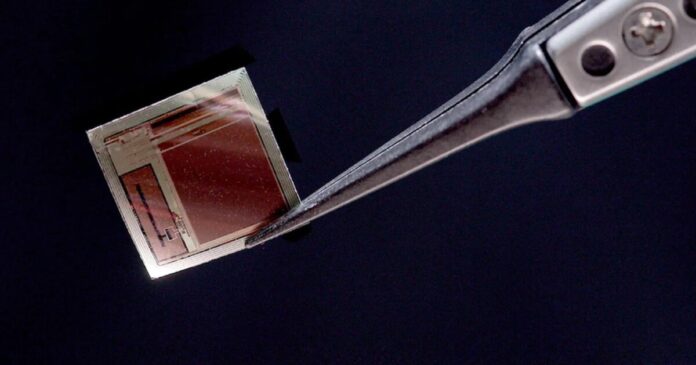

Combining three semiconductor technologies onto one chip, the high-bandwidth yet wireless BISC is a BCI on a single silicon chip a mere 50 micrometers thick. With 65,536 electrodes, 1,024 recording channels, and 16,384 stimulation channels, the complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) integrated circuit is less than a thousandth the volume of typical brain implants and, like a licked stamp, can curve to stick to almost any surface – in this case, that of the brain.

Because it’s so small and thin (even though it contains analogue components for recording and stimulation, plus a wireless power circuit and power management, a radio transceiver, and digital control electronics), the stamp-sized BISC can be implanted through a tiny opening in the skull. Its external relay station can connect the BISC to any computer with throughput of 100 Mbps, a hundred times greater than that of any rival wireless BCI.

Using AI models, the BISC decodes high-bandwidth recordings to identify body motion, sensory information, brain states, and even intent. As Shepard explains, “By integrating everything on one piece of silicon, we’ve shown how brain interfaces can become smaller, safer, and dramatically more powerful.”

New Atlas has been extensively reporting on new developments in and opportunities from BCIs, a field rapidly expanding with new companies, which now include Kampto Neurotech from the Columbia and Stanford research team. As Nanyu Zeng, Kampto’s founder and a lead engineer on BISC, says, “This is a fundamentally different way of building BCI devices. In this way, BISC has technological capabilities that exceed those of competing devices by many orders of magnitude.” As such, Kampto is currently manufacturing BISCs for research use.

BCIs offer not only relief from physical and neurological impairments, but new and even superior control of computers and cybernetic devices. “This could change how we treat brain disorders, how we interface with machines, and ultimately how humans engage with AI,” says Shepard.

Source: Columbia University