Could you imagine being able to “feel” the images on your screen? UCSB researchers have made this sci-fi-like idea a reality. They’ve developed a display where pixels physically rise off the surface when activated by laser light.

Even our most advanced screens today have a limitation that makes them distinctly still feel like, well, screens: they’re flat. They can display entire worlds with a level of detail that just a couple of decades ago was incomprehensible, but we never quite feel what we see. That missing sense may be the next frontier between digital images and physical experience.

UCSB Engineering department

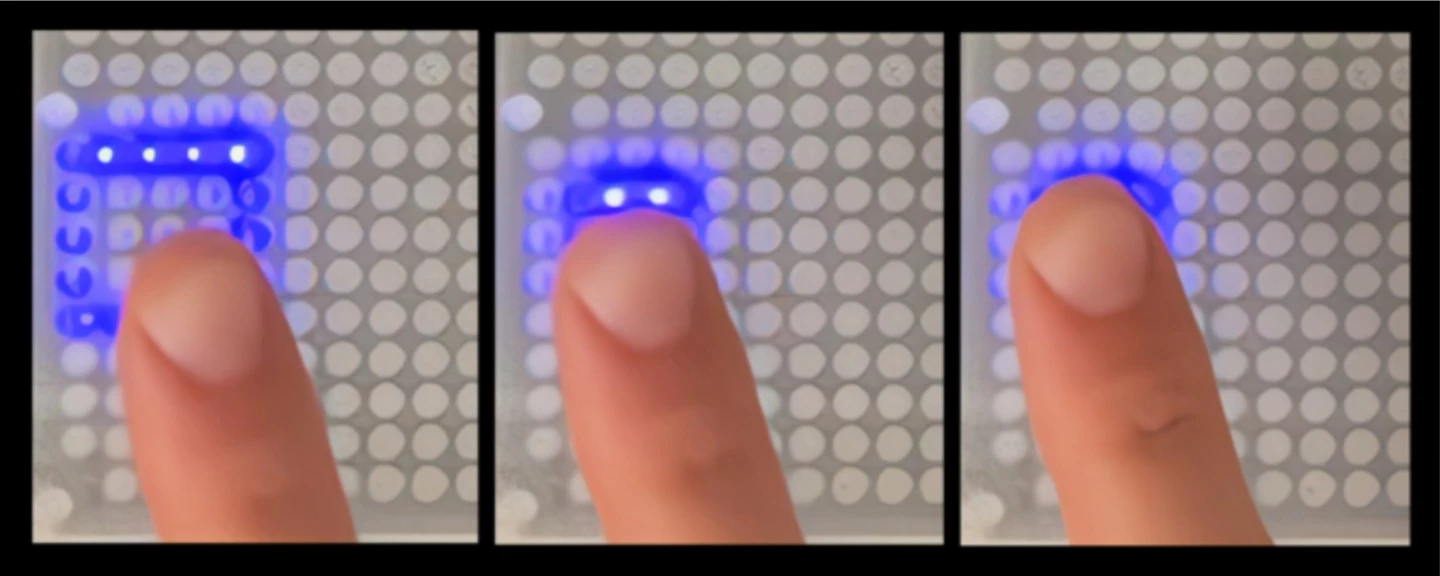

Researchers at UC Santa Barbara (UCSB) may have found a way across that frontier by turning light itself into touch. Their new display technology is made up of tiny pixels that rise into little bumps when they’re struck by controlled pulses of laser light. Images are given a whole new dimension; they literally lift off the surface, forming shapes you can trace with your fingertips.

It’s a compelling concept. What if anything you could see on a screen, you could also feel?

In 2021, UCSB professor Yon Visell challenged PhD researcher Max Linnander to investigate this very question: could light be made tactile?

Leading the research in Professor Visell’s RE Touch Lab, and under his guidance, Linnander saw a breakthrough in late 2022. A single pixel popped upward under a flash of laser light, sending a tactile pulse that was very much noticeable to Professor Visell’s fingertips. “That was a special moment – the moment we knew the core idea could work,” Visell said. A single pixel was enough to prove that touchable graphics might be possible just by shining light.

UCSB Engineering department

At the heart of this invention are tiny optotactile pixels, which are millimeter-scale cells built with a thin graphite film stretched above a small air cavity. When a quick pulse of laser light hits a pixel, the film heats up, causing the trapped air to expand, making the surface bulge upward for a split second, by about a millimeter (0.04 in).

“The pixels respond very rapidly, so what one feels is quite crisp in time” Visell explained to New Atlas. “While the pixels deflect outward, this occurs very rapidly. The sensation is not one of a bump, but rather of a small animated haptic quantum under your finger.”

Since the laser beam offers both power and control, the surface doesn’t need any wires or other additional electronics under each pixel. A scanning system sweeps the light across the array at high speed, activating one pixel after another.

UCSB Engineering department

So far, the UCSB team has built arrays with over 1,500 independently-activated tactile pixels that respond in just 2 to 100 milliseconds. That level of responsiveness means that moving shapes and characters always seem smooth, and never feel choppy or laggy.

This high-density, high-speed setup could open the door to an entirely new form of tactile storytelling. Test users could follow a moving bump across their screens, identify shapes and spatial layouts, and perceive sequences over time (essentially, tactile animation).

Conceptually, it’s a simple interface; but it already feels like the surface is “alive” under your hands.

As a sighted person, it does initially feel like a delightful novelty: game interfaces that literally push back, or maps where you can feel the elevation of contour lines. But the more I think about it, the more it feels like it could have profound potential for people who navigate the world through touch.

Imagine reading a science textbook where the diagrams reshape themselves under your fingertips, or a map that guides you along raised paths that move as directions change.

This begins to look like a sort of “animated Braille” – tactile information that updates, morphs, and tells a story in real-time. It could make digital learning faster and richer for blind users who currently rely on static tactile graphics that either can’t adapt on the fly, or can only do so under rigid constraints.

3DPhotoWorks

Larger displays could bring this into everyday settings, too. Car dashboards with controls that only appear when they’re needed, schoolbooks and maps that physically animate concepts.

When we reached out to Professor Visell, he spoke of one entirely different, and particularly interesting use case: enabling large-scale architectural walls that integrate optotactile pixels. The possibilities are endless, and despite how sci-fi it may seem, it’s not far out of reach.

“[Architectural walls] in offices, homes, or hospitals – that integrate interactive, haptic displays, reconfigurable controllers, or interfaces,” he said by way of example. “This possibility is relevant because the complexity of our technology remains manageable as the display dimensions, and number of pixels, grow, and because of the low cost of the materials. One can reproduce our research prototypes, even in bespoke form, for low hundreds of dollars.”

A paper on the research project has been published in the journal Science Robotics.

The invention is currently in its infancy, and there are challenges ahead: managing heat, ensuring durability, and scaling the resolution to match the multi-million pixel displays we’re used to. But the trajectory feels promising.

Touch and sight have always lived in separate digital worlds. We input with touch, and consume outputs with sight. With optotactile pixels, this separation may just be narrowing. As the UCSB researchers put it, someday soon, anything you see, you may also feel.

Source: UCSB