There’s an old saying in Urdu: Zaroorat ijaad ki maa hai (necessity is the mother of all inventions). I would often hear it as a child growing up in Pakistan.

I’ve always been fascinated by how some phrases leap across languages without losing their truth.

You see, survival has a universal dialect, and here, behind the castle walls of New Jersey State Prison (NJSP), necessity isn’t just a mother, it’s a warden, a foreman, and a constant whisper in your ear.

Pennies on the dollar

Like the chains and hooks once used for corporal punishment in the basement of the “Warden’s House” at NJSP, prison labour is a relic of another time. It is a system that still smells faintly of chain gangs and sweat-soaked fields.

Here at NJSP, we work because we’re told to, for pennies on the dollar.

According to the Prison Policy Initiative (PPI), a non-profit that researches mass criminalisation in the US, prisoners can earn as little as $0.86 per day, with those in skilled work – like plumbers, electricians and clerks – making barely a few dollars per day.

Meanwhile, American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) research shows that many states pay between $0.15 and $0.52 per hour for cleaning and maintenance jobs, such as sanitation work, with some states paying prisoners nothing at all.

The Department of Corrections budget runs in the billions, but prisoners can work every day of the year and still only make enough to choose between soap or soup when ordering from the commissary.

According to the PPI, prisons collect approximately $2.9bn annually from sales at the commissary and prisoners’ phone calls. Meanwhile, an investigation in The Appeal, a publication focusing on the US legal system, found that commissary prices are often five times higher than prices outside prison, with markups soaring as high as 600 percent for something like a denture container.

With costs like these, prisoners have had to create a second economy just to survive inside. We call it the “hustle” – not in the Wall Street sense, but in the purest form of making something out of nothing.

The tailor

I met “Jack”, who works in a pantry, a man who prefers to keep his real name to himself for fear of reprisals. His job at the prison involves preparing meals for fellow prisoners. He works 365 days a year with no holidays, no sick time, and each month is paid a little over $100 into his prison account.

Jack doesn’t get money from his family on the outside. Most prisoners don’t. In fact, many actually support their loved ones outside through their prison hustles.

Jack stitches survival together with a needle and thread. He hems khakis, tapers shirts, and mends shoes for stamps. This prison currency is bought through the commissary or traded among prisoners as hard currency for buying and selling. One book has 10 stamps and costs about $8 in the commissary, but can cost more when traded between prisoners.

Two books of stamps get you a tailored “set” (pants and a shirt or two shirts), and it’s four stamps (about $3) to raise your pant cuffs above the ankles, a popular request among Muslim brothers here. Jack won’t say how much he earns a month, but it’s more than what he makes prepping meals.

Water is his biggest expense. “The tap water here burns my stomach,” he told me. “Tastes like metal.”

He buys a case of 24, 16oz (470ml) bottles of water for $6 (about eight stamps). Only three cases are allowed per inmate at a time, and we can only order from the commissary twice a month. He tries to ration, but when he runs out – or water isn’t available at the commissary – he needs to fork out more money to buy bottles from other prisoners who sell at higher prices.

“The funny thing,” he said, not smiling, “is that they [the prison] give the officers water filters.”

The corner store

On another tier, Josh runs what you might call a corner store without a corner. He sells and trades food for a profit – chili pouches or blocks of cheese from the commissary, peppers smuggled out of the kitchen. The commissary may run out of items or place limits on how many prisoners can buy, so the prisoners go to Josh. But they also go to him for other things – staplers for legal work, shoes, or cash. They trade prison stamps for their purchase. The exchange rate and prices fluctuate depending on supply and demand, but there’s always a profit. A pack of 24 cookies bought at the commissary for $4 may sell for anywhere between $5 and $12. It’s often more profitable to sell loose cookies.

Josh’s system is pure street business. He buys in bulk from the kitchen workers who steal small quantities from the pantries, and when a prisoner makes an order, he smuggles the item to them immediately – usually via a “unit runner”. He sells with a markup, and offers credit at higher rates.

“It’s a cat-and-mouse game,” Josh explained. “The trick is to never keep anything in your cell. Too many haters.”

The “haters” might snitch, and get Josh in trouble. Sometimes, snitching itself is a hustle where police recruit a prisoner to spy and provide them with food, which they, in turn, sell.

Josh’s hustle lets him buy gifts for his children and cancer awareness T-shirts for his recovering mother, and keeps his phone account alive so he can speak to them.

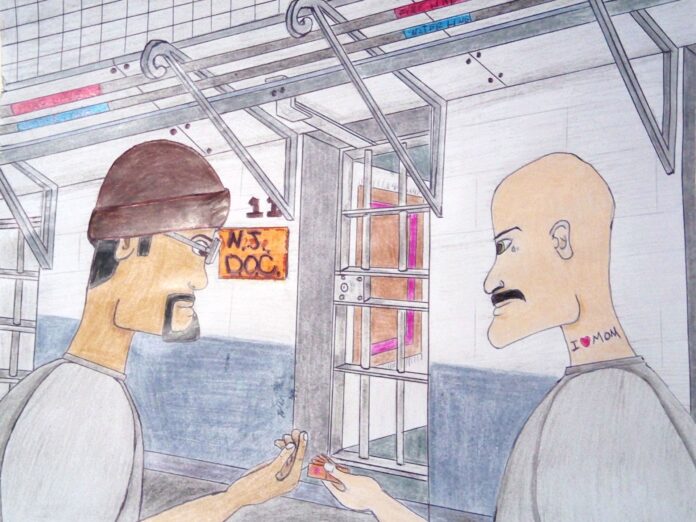

And then there’s 52-year-old Martin Robles, who can fix anything. I call him “Mr Fix It”. He can do it all: fans, electronics, clothing. In the summer, when fans burn out, he bypasses the fuse (which often breaks due to power fluctuations) for the price of two books of stamps. “You have to spend money to make money,” he said, explaining the cost of oil, glue, and sandpaper – the tools of his trade. He didn’t want to reveal how much he makes, but he is sought after in prison. He says his hustle isn’t about survival so much as keeping his hands busy and his dignity intact.

The hustles keep turning

Each of these men works in the official prison economy, and then works again in the shadow one. In both, they are underpaid, undersupplied, and overwatched. The hustle isn’t about greed. It’s about staying alive, staying connected, and, sometimes, sending a birthday gift to a goddaughter to remind her, and more importantly, yourself, that you still exist beyond these walls.

In here, we don’t have much. What we do have is time, pressure and the kind of hunger that sharpens the mind. So we make do. We turn scraps into tools, boredom into ritual. Behind these walls, necessity will keep birthing inventions. And the hustles will keep turning, one quiet transaction at a time.

This is the second story in a three-part series on how prisoners are taking on the US justice system through law, prison hustles and hard-won education.

Read the first story here: How I’m fighting the US prison system from the inside

Tariq MaQbool is a prisoner at New Jersey State Prison (NJSP), where he has been held since 2005. He is a contributor to various publications, including Al Jazeera English, where he has written about the trauma of solitary confinement (he has spent a total of more than two years in isolation) and what it means to be a Muslim prisoner inside a US prison.

Martin Robles is also a prisoner at NJSP. These illustrations were made using lead and coloured pencils. As he has limited art supplies, Robles used folded squares of toilet paper to blend the pigments into different shades and colours.