Each year, vast blooms of phytoplankton spread across the Southern Ocean, drawing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and fueling Antarctica’s marine food web. For decades, scientists have attributed these pulses of life to familiar forces – sunlight, winds, and ocean circulation. But new research suggests another, far less visible driver may be at work: earthquakes beneath the seafloor, whose activity may be influencing ocean surface conditions.

In a new study led by researchers at Stanford University, scientists examined how deep-ocean earthquakes beneath the Southern Ocean may be influencing surface ecosystems around Antarctica. By combining satellite observations with seismic records, the team found that when earthquakes of magnitude 5 or greater occurred in the months leading up to the Southern Hemisphere summer, the region’s peak phytoplankton growth season, the resulting blooms became significantly denser and more productive. When the researchers tracked these blooms over time, they observed large fluctuations in bloom size across different years.

“When looking back over satellite observations of this bloom, we’ve seen it swell to the size of the state of California or down to the size of Delaware,” said lead study author Casey Schine, who conducted some of the research as a PhD student at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. “Our study ultimately showed that the main factor controlling the size of this annual phytoplankton bloom was the amount of seismic activity in the preceding few months.”

The researchers found that seismic activity may intensify hydrothermal systems on the seafloor, potentially boosting the release of nutrient-rich fluids into surrounding waters.

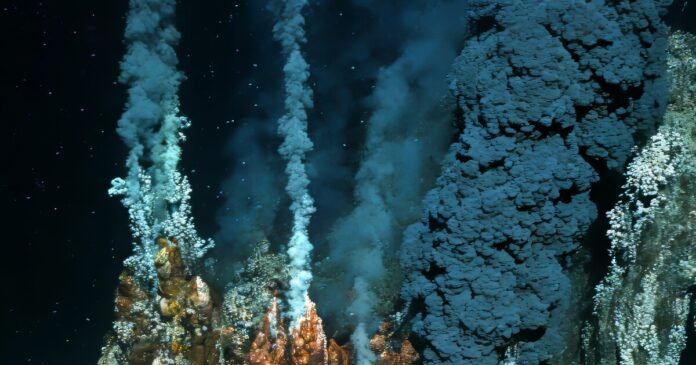

But what exactly are hydrothermal vents, and how do earthquakes impact nutrient dispersion?

Think of hydrothermal vents as the ocean’s natural plumbing system. As seawater seeps down into Earth’s crust, it becomes superheated, freeing up dissolved minerals and metals, including iron, manganese, and other trace nutrients. That mineral-rich fluid is then released back into the ocean, where it helps feed marine ecosystems, including microscopic phytoplankton that form the foundation of the Southern Ocean food web.

Under normal conditions, much of this material remains trapped in deep waters. But when earthquakes rupture the crust beneath the Southern Ocean, those hydrothermal systems briefly intensify, releasing pulses of iron that are mixed upward through the water column.

It is less like a steady current and more like stirring a long-settled pot; a single jolt can mobilize nutrients from the seafloor into surrounding waters, enriching the ecosystem above. Once that iron reaches surface waters, it becomes available to phytoplankton, microscopic organisms that depend on the nutrient to fuel growth.

“This is the first ever study to document a direct relationship between earthquake activity at the bottom of the ocean and phytoplankton growth at the surface,” said Kevin Arrigo, senior study author.

The study also challenges long-standing assumptions about how quickly hydrothermal iron can reach the ocean surface. The researchers found that iron released from vents would need to travel nearly 6,000 feet (1,830 m) upward to become available to phytoplankton within weeks to a few months, far faster than the prevailing view that such material would take decades to reach surface waters.

The downstream biological effects of this process are significant. Iron is a critical nutrient for phytoplankton growth, yet across much of the Southern Ocean it remains in short supply. Even when sunlight and other nutrients are abundant, limited iron availability can keep plankton populations in check.

This is why iron released during seismic events appears to have such a strong impact, allowing phytoplankton blooms to expand rapidly across surface waters. Those blooms then ripple through the food web, supporting zooplankton, fish, and higher predators, while also increasing the ocean’s capacity to absorb carbon from the atmosphere.

As phytoplankton grow and multiply, they pull increasing amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis, incorporating that carbon into their cells. This process forms the foundation of what scientists call the biological carbon pump. When blooms expand, more carbon is removed from surface waters and eventually transported into deeper layers of the ocean as organisms die or are consumed.

How much this earthquake-driven mechanism contributes to global carbon cycling remains an open question.

“There are many other places across the world where hydrothermal vents spew trace metals into the ocean and that could support enhanced phytoplankton growth and carbon uptake,” said Arrigo. However, he noted that these regions remain difficult to sample, making it hard to gauge how much these systems really matter at the planetary scale.

While earthquakes are not a continuous or predictable source of nutrients, the study highlights their role as an episodic force that has largely been overlooked in models of how the ocean responds to physical change. Most existing frameworks focus on winds, currents, and seasonal mixing, processes that operate continuously.

Seismic events, by contrast, are rare and abrupt, yet capable of producing disproportionately large biological responses when they occur. Accounting for these sudden inputs adds nuance to how scientists think about variability in ocean productivity. And in particular, regions like the Southern Ocean where ecosystems are known to be constrained by nutrient availability.

Going forward, the researchers say the next challenge is to better understand and track how seismic activity interacts with deep-ocean circulation and nutrient transport, and to determine where else this hidden connection between geology and biology might be operating. As monitoring tools improve, earthquakes may become another variable scientists must consider when mapping how the ocean responds to change.

This study was published in Nature Geoscience.