Hidden inside the narrow growth rings of Pyrenees trees lies the strongest evidence yet for what set the Black Death in motion. For the first time, researchers have combined high-resolution climate reconstructions with medieval records to draw a direct connection between a sudden climatic shock and the arrival of the plague in Europe, where it killed tens of millions between 1347 and 1353.

The new study, from the University of Cambridge and the Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe (GWZO) in Leipzig, has argued that the Black Death’s devastating impact began not with a pathogen alone but a “perfect storm” of environmental and human stressors. Specifically, a volcanic eruption – or cluster of eruptions – around 1345 triggered several years of abnormally cold, wet summers across southern Europe.

Ulf Büntgen

“This is something I’ve wanted to understand for a long time,” said Professor Ulf Büntgen from Cambridge’s Department of Geography. “What were the drivers of the onset and transmission of the Black Death, and how unusual were they? Why did it happen at this exact time and place in European history? It’s such an interesting question, but it’s one no-one can answer alone.”

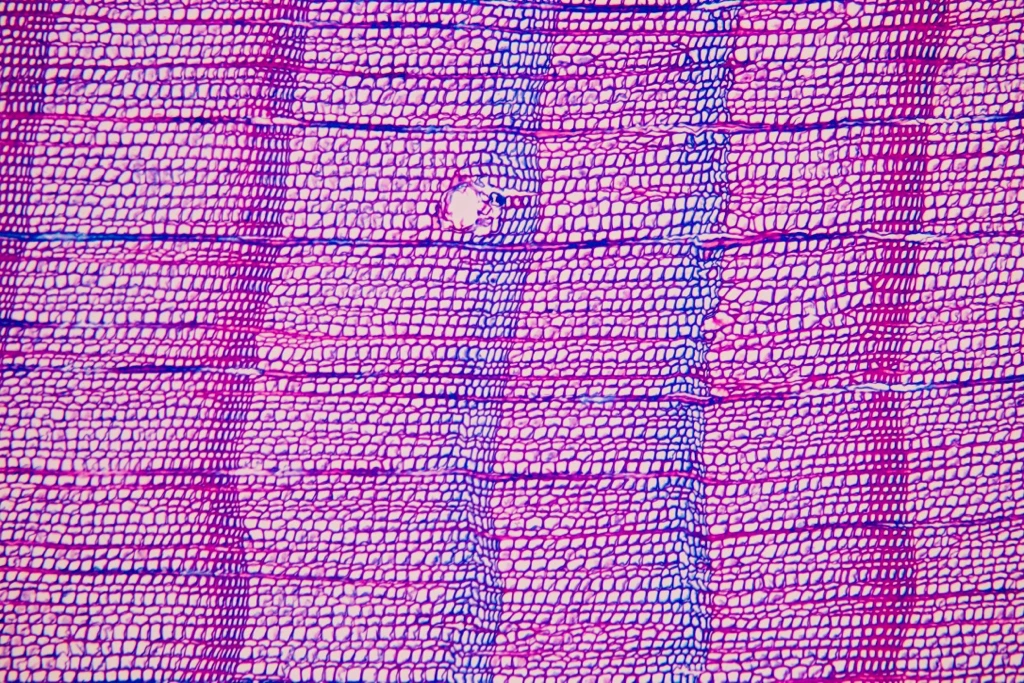

These conditions are recorded in the distinctive “blue rings” found in trunk sequences from trees in the Spanish Pyrenees, which indicate severely reduced growth during 1345, 1346 and 1347. A single poor summer can be explained away, but three consecutive ones bear the hallmarks of a major volcanic event. And contemporary accounts describing persistent cloudiness and dark lunar eclipses further support this argument.

Ulf Büntgen

“We looked into the period before the Black Death with regard to food security systems and recurring famines, which was important to put the situation after 1345 in context,” said Martin Bauch, a historian of medieval climate and epidemiology at GWZO. “We wanted to look at the climate, environmental and economic factors together, so we could more fully understand what triggered the onset of the second plague pandemic in Europe.”

This climatic disruption and onset of cold then caused widespread harvest failures around the Mediterranean. Faced with the threat of famine, Italy’s maritime regions of Venice, Genoa and Pisa activated their long-distance trade networks to secure grain from the Mongol territories of the Golden Horde around the Sea of Azov. These supply lines had been built over a century and, in 1347, prevented mass starvation. However, they also transported the plague’s vectors – fleas.

“For more than a century, these powerful Italian city states had established long-distance trade routes across the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, allowing them to activate a highly efficient system to prevent starvation,” said Bauch. “But ultimately, these would inadvertently lead to a far bigger catastrophe.”

The researchers believe that ships arriving with grain also carried fleas infected with the bacterium Yersinia pestis. While it’s still not known where this bacterium originated, ancient DNA points to a natural reservoir in wild gerbils in central Asia. But once these fleas disembarked in Mediterranean ports, they jumped from rodents to humans and ignited the first, deadliest wave of the pandemic. From there, the Black Death quickly tore across Europe.

To better understand the timeline, the research team paired environmental reconstructions with evidence of food-security systems and trade behavior before and after 1345. They found that the cities forced to import grain during those climate-driven shortages were the same places that were hit early and intensely by the Black Death. Meanwhile, major cities that did not rely on imports largely escaped the pandemic’s initial deadly wave.

“Many Italian cities, even large ones like Milan and Rome, were most probably not affected by the Black Death, apparently because they did not need to import grain after 1345,” said Bauch. “The climate-famine-grain connection has potential for explaining other plague waves.”

Bibliothèque Nationale de France

The researchers argue that the Black Death wasn’t triggered by a single factor but by that “perfect storm” of climate, agriculture, trade, ecology and human decision-making – an early example of how globalized systems can ultimately amplify biological risk. (We don’t have to look too far back in the history books to see how modern modes of transport enabled COVID-19 to spread around the world in just weeks.) Now, as climate change reshapes ecosystems and threatens food security, the probability that zoonotic pathogens will spill over and spread through globalized trade networks is increasing.

“Although the coincidence of factors that contributed to the Black Death seems rare, the probability of zoonotic diseases emerging under climate change and translating into pandemics is likely to increase in a globalized world,” said Büntgen. “This is especially relevant given our recent experiences with COVID-19.”

The researchers add that modern pandemic risk assessments should also incorporate knowledge from historical examples of the interactions between climate, disease and society – even those from nearly 700 years ago.

And while the Black Death decimated Europe’s population, it also fundamentally reshaped the social and political landscape of the continent. With mortality rates estimated at 30–50%, labor shortages became so severe that surviving workers could demand higher wages and greater mobility, accelerating the breakdown of feudal systems and weakening the power of the elite class. Agricultural work shifted, and inheritance laws were upended as vast amounts of property changed hands in a single generation. The collapse of traditional authority also fueled religious upheaval, persecution, widespread social unrest and the eventual rise of new institutions. In many regions, the demographic shock paved the way for massive economic restructuring, urban growth and, over the longer term, conditions that would set the stage for the Renaissance. But perhaps that’s a story for another time.

The research was published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

Source: University of Cambridge