Because of industrial climate chaos, catastrophic economic inequality, war and displacement, there is, as the United Nations puts it succinctly, a global food crisis in 68 countries, with 318 million people facing acute hunger. Simultaneous famines in two countries (Palestine and Sudan) – which the UN calls “a devastating first this century” – threaten millions of lives.

While it’s clear that crises caused by economic and political decision makers are most easily solved by “un-deciding” them, until those decision-makers develop empathy, the rest of humanity will need to create and implement other solutions to starvation. And fortunately, researchers in the Jacobs School of Engineering at the University of California San Diego are doing just that.

In their ACS Materials Letters paper “Polynorbornene Spray Coating to Enhance Plant Health,” lead author Patrick Opdensteinen and colleagues reveal that their new tool for global food security is a polymer functioning as a spray-on armor that helps plants fight destructive bacteria while surviving drought.

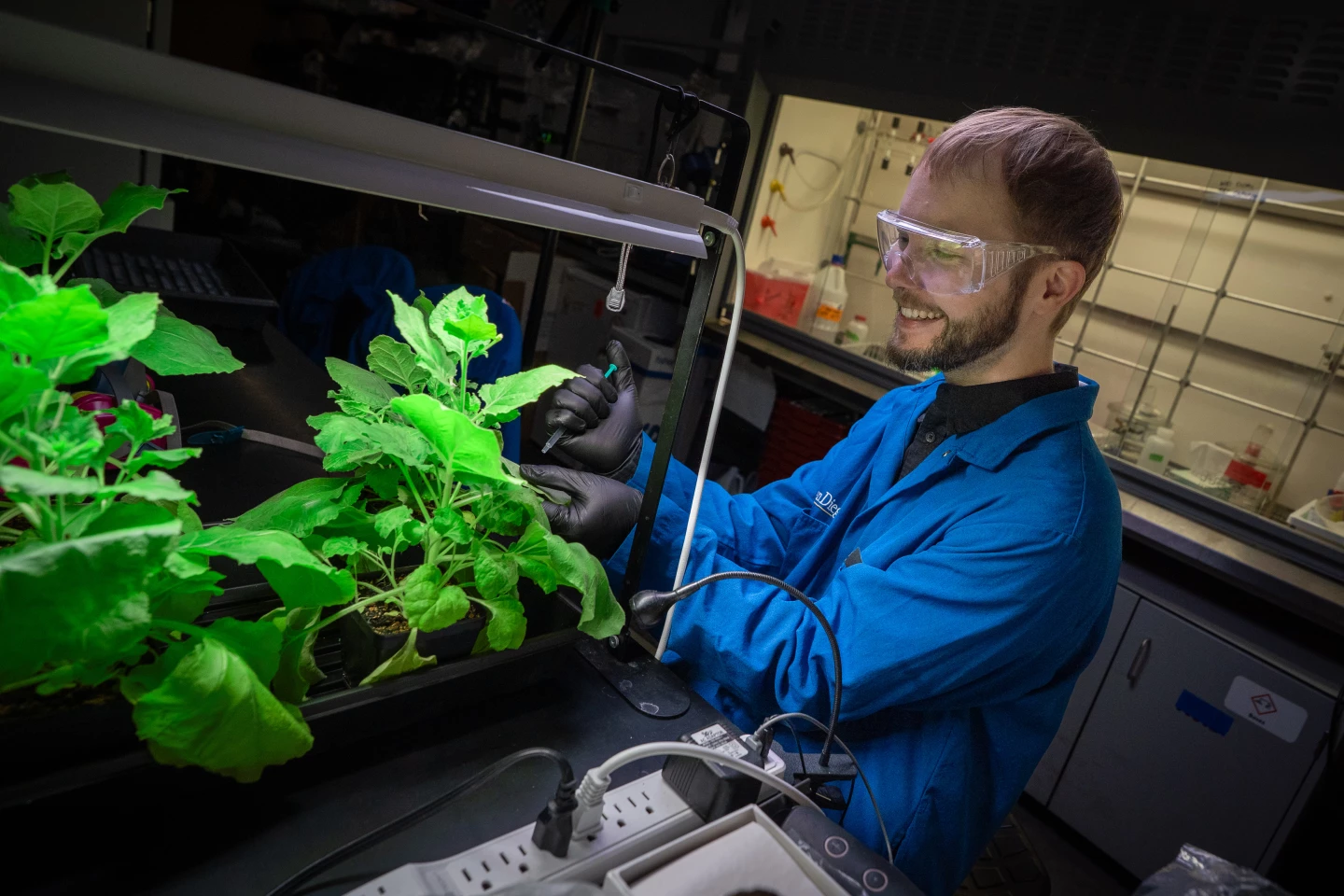

David Baillot/UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering

Just as human beings face illness and death from a range of bacteria, so too do plants (even though, as New Atlas has reported, some bacteria also help plants and humans). But when those plants are the crops that humans need to survive, that bacterial threat means chaos for global security and individual lives.

Bacterial plant diseases include speck (a winter-surviving infection that attacks tomatoes), canker (which damages fruit trees including those producing apples and peaches), and blight (which rots melons, cucumbers, pumpkins, squash, peppers, tomatoes, eggplants, beans, and more). Even worse, climate chaos allows such bacteria to invade territories whose previously low temperatures would have stopped cold.

So, how does the spray work?

Scientists from UC San Diego’s Aiiso Yufeng Li Family Department of Chemical and Nano Engineering and the Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (MRSEC) collaborated to construct a synthetic polymer containing positively charged chemical groups. By adjusting a typical polymer synthesis to work in water, the researchers created the gas-permeable polymer polynorbornene, which is harmless to plants but which weakens the cell membranes of a various harmful bacteria.

“Typically, polymers are synthesized using organic solvents that are toxic to plants,” said co-first author Luis Palomino, a PhD candidate in chemical and nano engineering. “What we did differently here is we made the polymer in buffer conditions in water. That allowed us to make a spray formulation that’s more biocompatible with plants. We can easily dissolve the polymer to the right concentration in water and just spray it on.”

One of the unexpected benefits was that the spray-on armor didn’t need to cover the entire plant, or even the entire leaf – which was akin to discovering that an armored glove makes a bullet-proof vest unnecessary. “We can spray just a small part of the leaf,” says Opdensteinen, “and that translates to bacterial immunity for the whole plant. That was a really cool outcome.”

David Baillot/UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering

But why does such protection exist? If the researchers’ speculation is correct, it may be that the stress response of sprayed leaves creates a small, temporary, and harmless increase in hydrogen peroxide, which may activate other defenses in the plant.

But one of the best results of the UC San Diego experiment was improved plant resistance to drought. After four days of imposed thirst, untreated plants withered more than treated ones, which remained healthy, perhaps because the spray-on polymer was preventing water loss (like a Dune stillsuit for plants) while improving stress responses at the molecular level.

In the future, Opdensteinen and his colleagues will seek to increase their polymer’s biodegradability, while investigating the degree of its potential toxicity. “Our hope,” he says, “is to use this in the field to benefit agriculture, and this is the first step. There’s a lot of potential for plant protection.”