We generally associate the origins of mathematical thinking with the emergence of writing, about five to six thousand years ago. However, a new study challenges this assumption looking at floral designs found on the painted pottery sherds from the Halafian sites across northern Mesopotamia, dating back 8000 years.

“The study suggests that mathematical cognition developed well before writing, embedded in craft traditions such as pottery painting and seal engraving. It shows that complex abstract thinking was already present in Neolithic communities,” says Laurent Davin, an archaeologist at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who was not involved in the study.

Photos courtesy of Yosef Garfinkel

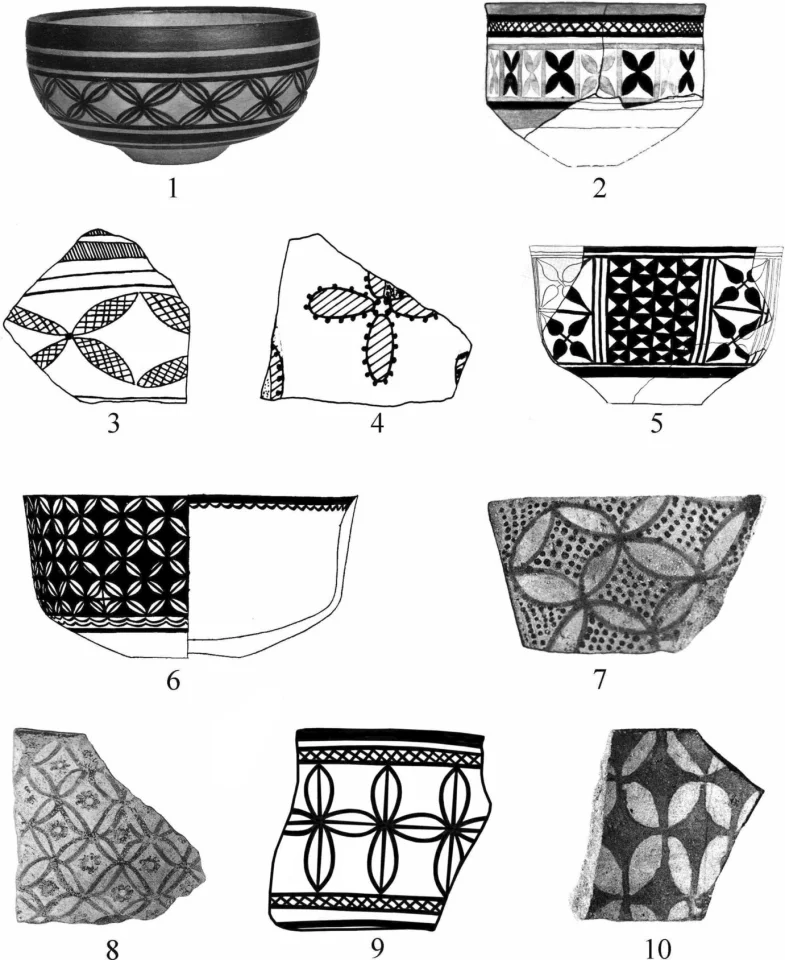

The earliest artistic expression in the European Upper Paleolithic era dates back to 40,000 BCE. Although plants played a central role in subsistence for centuries, Neolithic communities heavily relied on human and animal figures, with scarce traces of plant visual representation, such as flowers, shrubs, and branches. The new paper, published in the Journal of World Prehistory, suggests that “to the best of our knowledge,” the use of floral designs was introduced in Halafian culture (6200-5500 BCE).

In an email to New Atlas Davin says that the painted pottery of the Halafian culture represents the earliest systematic and widespread use of vegetal motifs in prehistoric art.

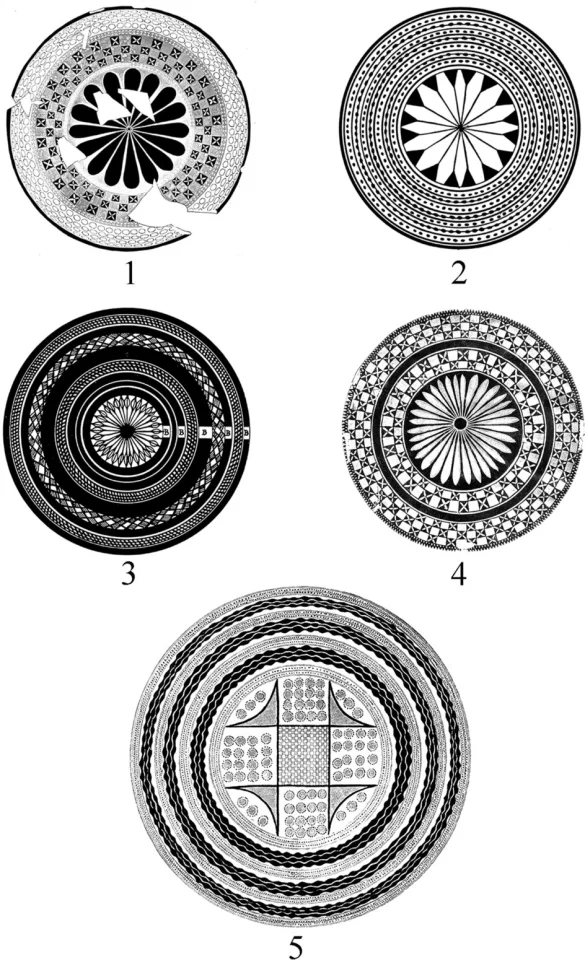

The new study, led by Yosef Garfinkel, examined 29 Halafian sites and reviewed thousands of painted pottery fragments. To get a better sense of vegetal patterns, the team classified the motifs into four categories: flowers, shrubs, branches, and trees. They found that flowers were by far the most common vegetal element, identified in 375 sherds, rendered with precision and symmetry.

Photos courtesy of Yosef Garfinkel

The flower petals, depicted in motifs, followed a specific geometric sequence: 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64, i.e., a mathematical geometric progression in multiples of two, not a random artistic choice. This repeated, precise division points to an understanding of geometric sequences, symmetry, and controlled spatial subdivision.

Additionally, the Halafian artists did paint flowers with 6, 7, and 13, but this appears to be the result of less skilled craftsmanship.

Garfinkel told New Atlas that the article contributes in two important ways to human cognitive evolution: first, by documenting the first appearance of plant motifs in art, including flowers, branches, shrubs, and trees, and second, by indicating mathematical knowledge in prehistory through repeated petal counts of 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64.

Photos courtesy of Yosef Garfinkel

Photos courtesy of Yosef Garfinkel

The paper argues that this mathematical system may have emerged in response to the practical demands of the early villages. Precise partitioning would have been useful for equal sharing of crops and other resources.

“Taken together, the findings reposition Halafian art as evidence for an important cognitive transformation: the integration of aesthetic appreciation, botanical awareness, and mathematical reasoning,” Davin concluded.

The study has been published in The Journal of World Prehistory.